The top floor of a medical building located on a hill afforded the exam room of the Women’s HIV Program multimillion-dollar views of... read more →

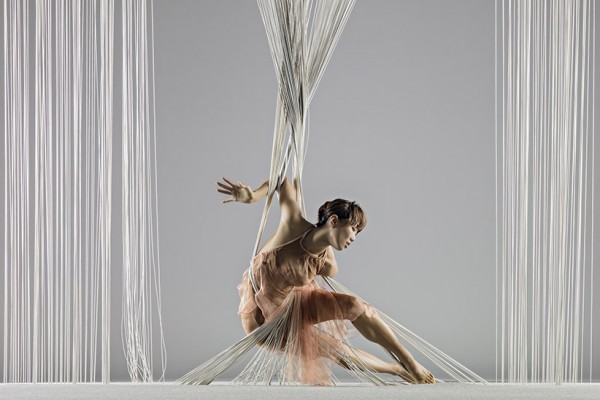

The Women's HIV Program at UCSF cordially invites you to the opening night of the Alonzo King Lines Ballet featuring performances by jazz legends Charles Lloyd & Jason Moran. A... read more →

San Francisco General Hospital Primary Care Grand Rounds: “From Treatment to Healing: The Promise of Trauma-informed Primary Care” a. San Francisco, CA – May 22, 2015

American Conference for the Treatment of HIV Invited Speaker a. Dallas, Texas – April 30-May 2, 2015 – "Trauma-informed care for special populations"

WHP teamed up with LINES Ballet once again this year on Friday, April 10, 2015 to raise awareness and support WHP's work at the front line of supporting powerful women living... read more →

Futures Without Violence National Conference on Domestic Violence a. Washington D.C. – March 18-22, 2015 b. Workshop presenter on Trauma-informed primary care for women living with HIV c. Workshop co-presenter... read more →

Keynote speaker at PWN-USA National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day Conference a. Oakland, California – March 5, 2015

AIDS United invited WHP Director Edward Machtinger to provide a testimony at a congressional briefing in recognition of Domestic Violence Awareness Month on October 14, 2014 in Washington D.C. The... read more →

Trauma-informed Primary Care Workshop at US Conference on AIDS a. San Diego, California – October 1-5, 2014

National Summit of HIV Positive Women Keynote Speaker a. Fort Walton, Florida – September 17-20, 2014